- The two best read for real market fundamentals (as opposed to USDAS's imaginary version) are futures spreads and basis.

- However, in old-crop winter wheat at this time of year there are no futures spreads and this year national average basis has gone a bit haywire.

- We've seen this before, and it will work itself out, most likely in line with a normal Rubber Band Disposition and Newsom's Market Rule #6.

This is a difficult time of year to get a good read on real supply and demand in winter wheat markets. March contracts have moved into delivery, leaving us with only the somewhat flighty May Chicago (SRW) and Kansas City (HRW) issues to track. And don’t bring up “there is always USDA reports…”. My thoughts on those are well known and unchanging. Remember, I’m interested in real world fundamentals rather than make-believe. My two preferred indicators are futures spreads, useful for both US and global supply and demand, and national average basis for the US side. Once March moves into delivery at the end of February, and July contracts are the first issue for new-crop, we have no old-crop only futures spread on which to rely. Yes, we can still study new-crop forward curves for a long-term view, but short-term we are partially blinded.

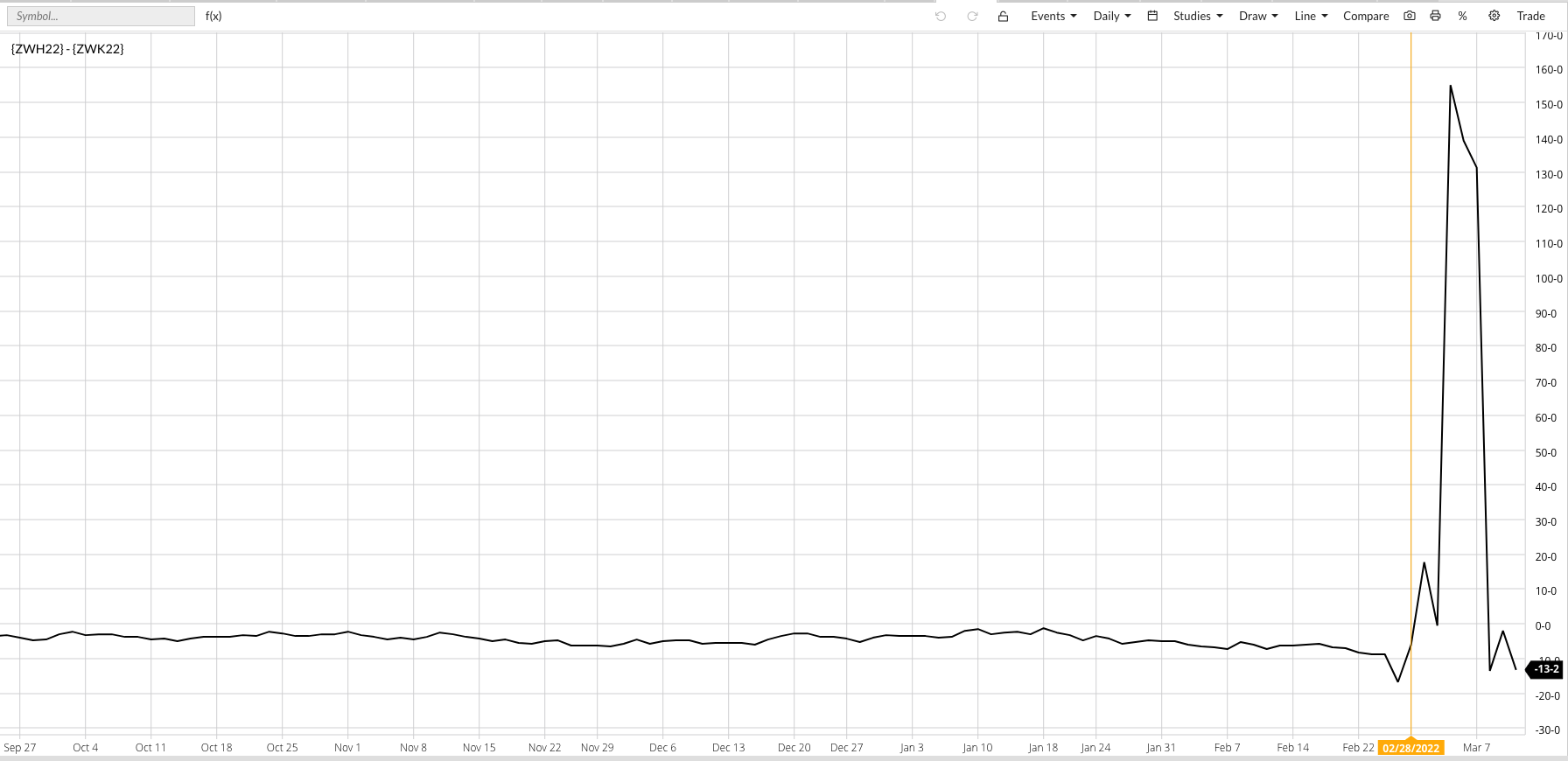

Then a year like 2022 comes along. Due to global events, in this case war in the Ukraine due to an invasion by Russian troops, we’ve seen the Chicago May contract (ZWK22) explode, leaving a trail of limit moves (both up and down) on its daily chart. A side note, total open interest in the market has fallen since peaking at 402,800 contracts on February 14. Russian troops launched a full-scale invasion on February 24. Chicago wheat was showing total open interest of 336,700 contracts at the close of Thursday, March 10. However, as we see on its daily chart, May Chicago has rallied from a close of $8.04 on Friday, February 18 to a high near $13.64 on March 8. This move of $5.60, a 70% increase, largely occurred without a significant change in US supply and demand. Just as everything was breaking loose in Ukraine, and the March issue was preparing to go into delivery on February 28, the March-May futures spread had been showing a neutral level of carry. Additionally, the cmdty National SRW Wheat Basis Index (ZWBAUS.CM) (SWBI, weighted national average) had been steadily gaining, with basis calculated at 45 cents under May futures in mid-February.

But when Russian troops poured into Ukraine and the Chicago futures market screamed higher, US merchandisers used their remaining defense against what was viewed as a fundamentally overpriced market (domestically) and crushed basis. Thursday’s calculation of the SWBI came in at $1.59 under May futures after Tuesday’s number had fallen to $2.06 under. Until the market settles down a bit we are largely left with no clear reads on real fundamentals.

We’ve seen this before, a number of times, most notably during 2008 when global drought had much the same effect on futures markets and national average basis fell to $2.00 under (though I don’t recall if that was HRW or SRW wheat). Newsom’s Rule #6 tells us, “Fundamentals win in the end”, and the bottom-line fundamental domestically is basis. Back in 2008, as basis was rocked while Chicago futures rolled to a high just short of $20.00 (week of February 25), we saw an extreme version of the Rubber Band Disposition[i]develop. Sure enough, the futures market eventually collapsed as traders scrambled for the exit.

But there is a key difference between the wheat markets of 2008 and 2022. Back then, new-crop futures spreads were also bearish, so much so many of them were running at more than 100% calculated full commercial carry, a factor that brought to life the still debated Variable Storage Rate program. This time around, new-crop 2022-2023 futures spreads are inverted in both Chicago and Kansas City. What does this tell us? The commercial side of the market still views long-term fundamentals as bullish, a factor that could, I repeat could, keep both Chicago and Kansas City (and possibly Minneapolis HRS) from a complete collapse. Again, fundamentals win in the end, and for now short-term US fundamentals indicated by national basis indexes are bearish, with an asterisk, while long-term global fundamentals indicated by futures spreads remain bullish.

[i] The Rubber Band Disposition exists when the two sides of the market, commercial and noncommercial, move in opposite directions. This stretches a market like a rubber band, until it ultimately breaks, snapping back to its base. And again, applying Newsom’s Market Rule #6 tells us markets tend to snap back toward the commercial side.

/Amazon%20-%20Image%20by%20bluestork%20via%20Shutterstock.jpg)

/Salesforce%20Inc%20HQ%20building-by%20JHVEPhoto%20via%20Shutterstock.jpg)

/Micron%20Technology%20Inc_logo%20and%20website-by%20Mojahid%20Mottakin%20via%20Shutterstock.jpg)